When We Fell

A short film made with Ben Spooner.

Landscapes gave way, a bird flew by.

A rolling canvas and one-take animation explores the wafer thin line between freedom and obliteration. Nothing can be taken for granted in this life. Everything changes, falls. The lived experience of this truth is captured by the journey of a bird through ever-shifting landscapes, on paper that also crumbles and rips before our very eyes. Accompanying this story is a dynamic soundtrack, with contemporary jazz influences. This original composition plays with chaos and simplicity, tension and ease, bringing forth another aspect of this visual and musical collaboration. Through hard times there is hope. Through destruction, growth.

Awards:

Official Selection:

Press:

Making Of:

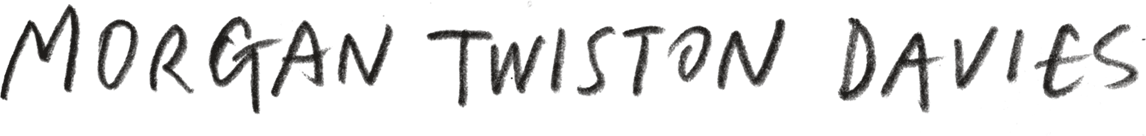

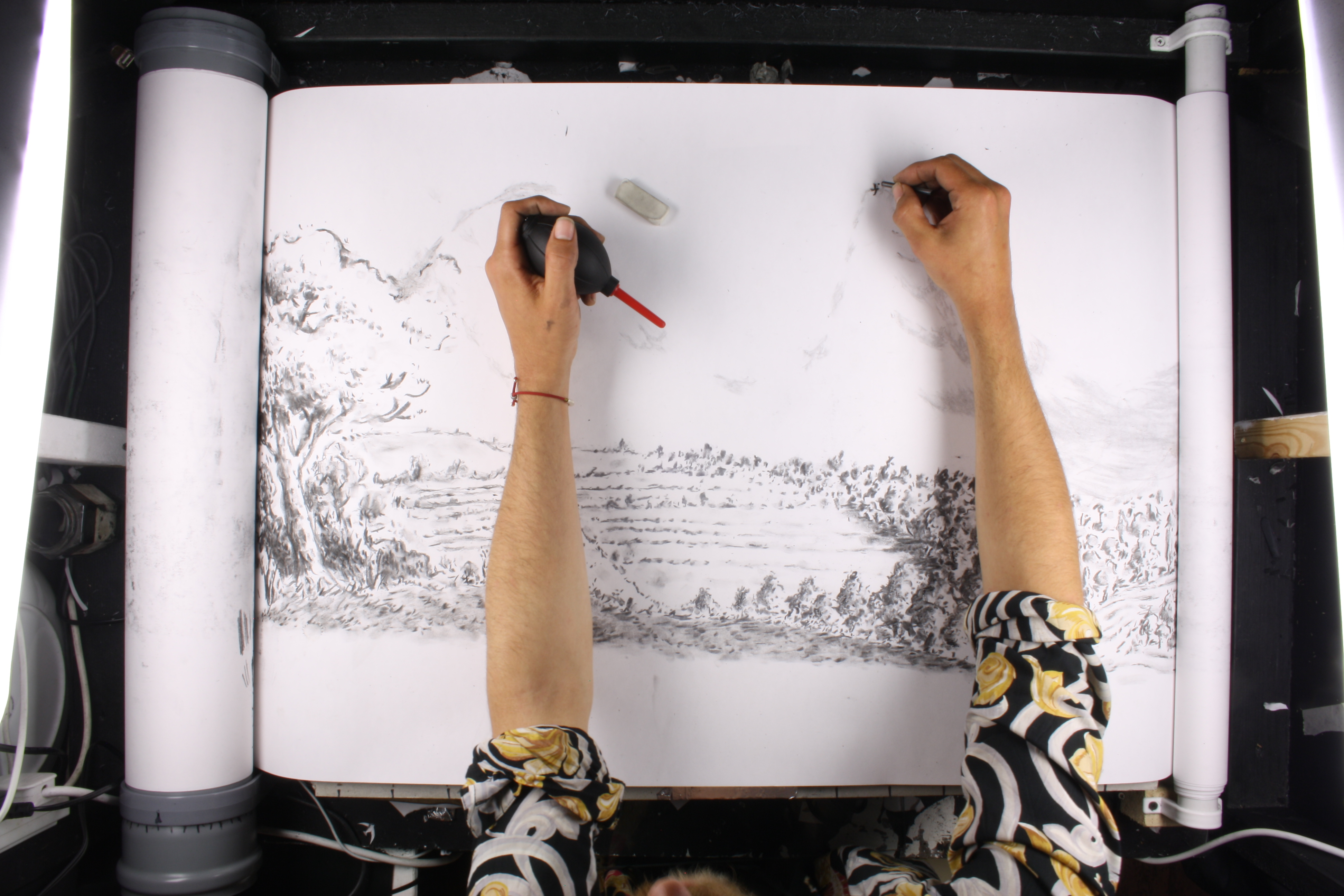

The concept was to animate the whole films spontaneously on one long piece of paper. In order to do so, I had to build a solid surface to support my paper, some sort of roller at either end to load the paper onto and a way to control where my paper is without it moving as I draw onto it (Fig.1).

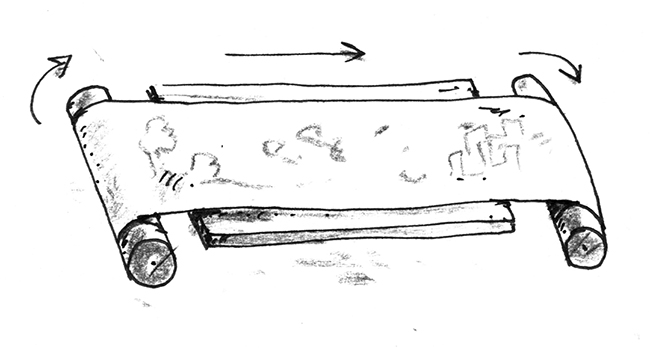

My solution was to use PVC drain pipes for the rollers, they’re cheap and the plastic clips that hold them in place are firm enough to stop the paper from moving when I don’t want it to and they automatically find the centre of rotation. I made marks at equal increments around the pipe and a reference point on the pipe clip to keep track of how far I turned the roller (Fig.4 A). My supportive surface was a raised drawing board, the top was just above the bottom of the rollers so the paper holds flat, then a black card that extends just past the edges of the wooden board to stop the paper roll from creasing and to act as my background when I tear the paper (Fig.2 B).

This setup fits into what I call my animation machine (Fig.3). A light-proof box I built on one side of my desk with a blackout curtain over an open side for access. There’s a top-down mounted camera (Canon Eos 1000D with the Canon ef-s 18-55mm lens), a street sourced TV that I’m using as my reference monitor (linked up to DragonFrame), two DIY kino-flo style lights (based on a modification of this design by the wonderful Edu Puertas) and an all important ventilation fan that I installed after sweat dripped on one too many frames and my snot turned black. With everything set up, we’re ready to start animating.

There were a couple of animation styles I used, mostly erasure animation, also a good chunk of cutout but I’m going to start with the technique present throughout, the stop motion camera movement. The actual camera stayed still, so all the movement was from the paper roll, turning one of the rollers to move everything along for each new frame. The further I turned the roller, the faster the camera movement. This was good for lateral movement, like a truck or pan, but in the film there are a few different camera orientations.

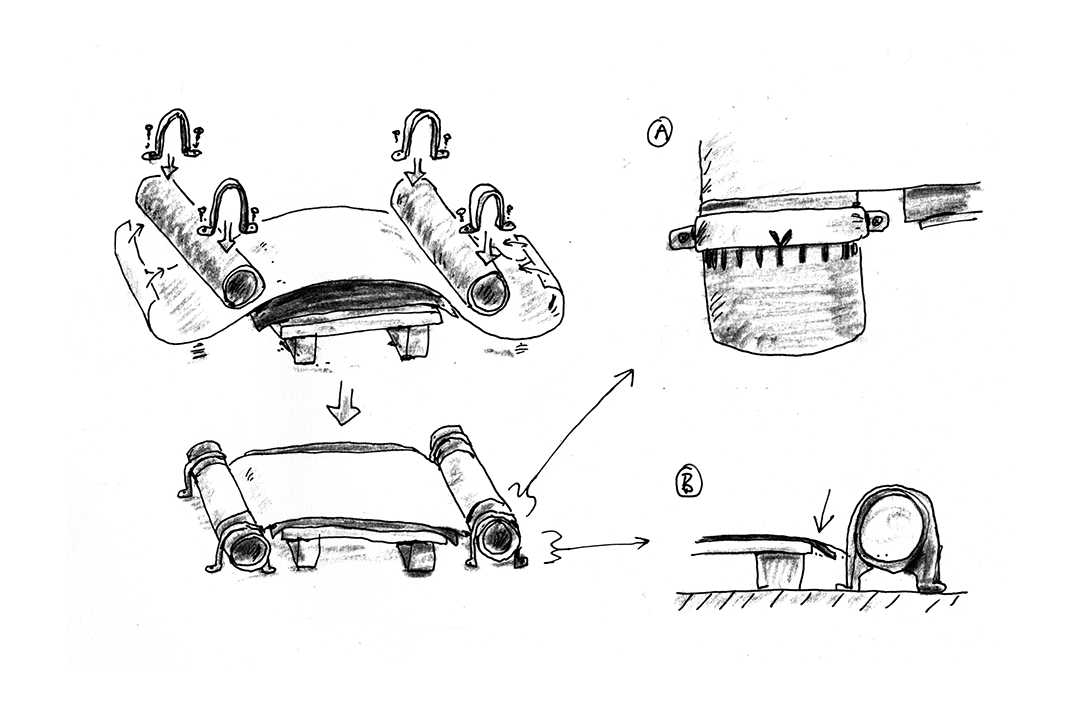

In order to achieve these orientations, it was a combination of warping the perspective of the background artwork I’m drawing, using more abstract mark making and playing with the speed of the camera movement to keep the eyes looking at what’s coming next rather than what’s leaving the screen. For some of the camera movements, such as when the camera goes through a car (Fig.4), it was a case of completely redrawing every frame.

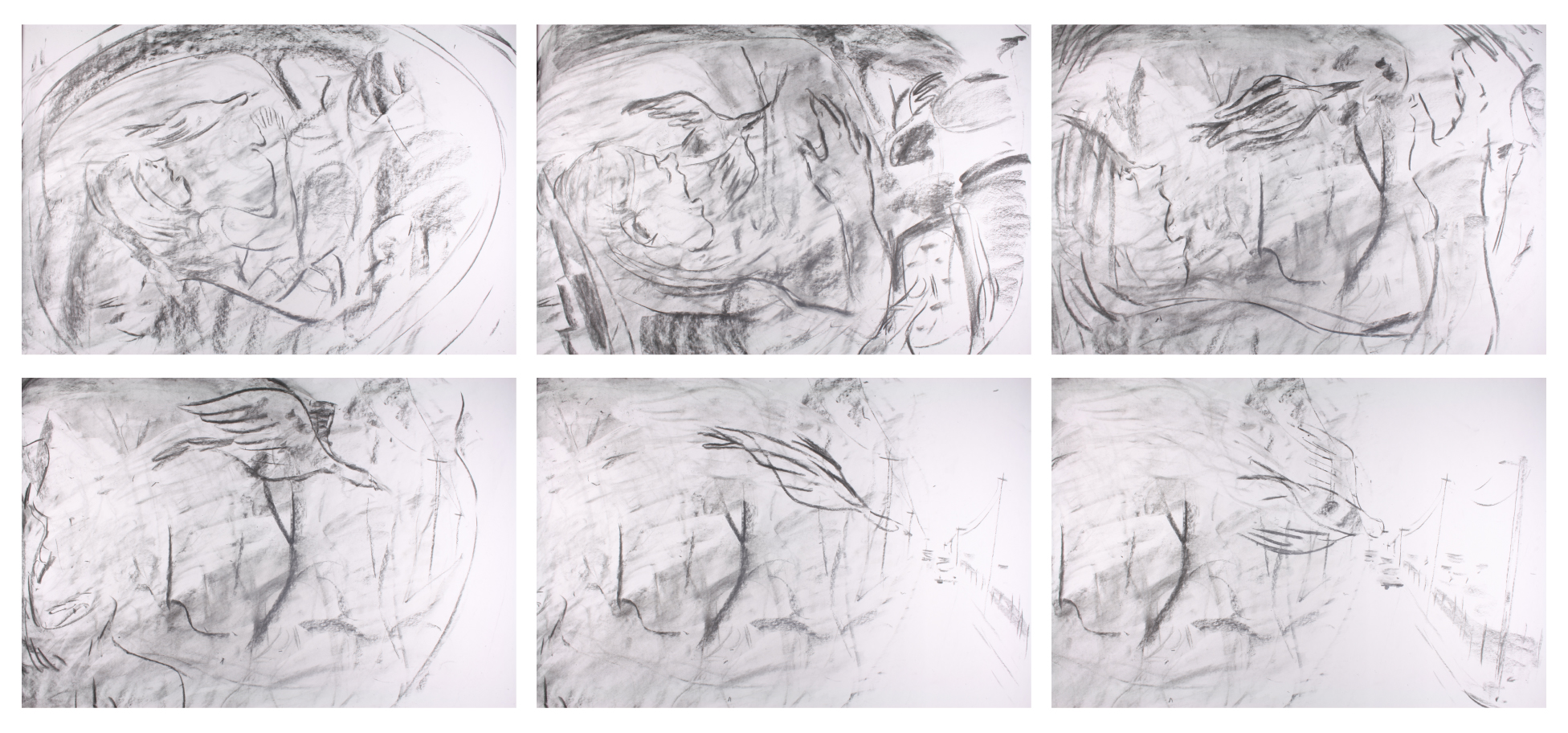

Which brings us on to erasure animation, the predominant technique used throughout the film. This is a form of hand drawn animation where all the frames of a scene are drawn on the same piece of paper. You draw your frame and capture it, then erase any part of the picture you want to move, draw those parts in a new position and capture the next frame (Fig.5). Then repeat. The erased frames leave behind a ghost you can use as a sort of onion skinning, but it also means you’re likely to be erasing big chunks of your background artwork when it’s drawn on the same piece of paper rather than composited later.

The background artwork, I should say, was also created frame by frame during the hand drawn stage. Once the opening shot was down, every time I rolled the camera forward it revealed a strip of blank paper that needed some artwork on it. So, before animating the characters, every frame I would draw anywhere between 0.5cm - 20cm of background at a time. Almost like a printer. So the process was this: move ‘camera’, draw background, erase and redraw characters, capture frame and repeat. There’s a few things to keep track of and if you don’t catch a mistake the moment you make it, you can’t turn back to fix it.

A much more forgiving process was the cutout stage. This technique uses mostly flat, cutout materials (in this instance, paper) that are moved every frame to create motion. Sometimes articulated puppets are made, but as my character was changing size when it flew around the scene, I opted for replacement animation. With this type of animation, instead of moving the same piece of paper, you replace it with a new one. I would draw out where I thought the bird was going to fly on a scrap piece of paper, cut out each of those little birds, then place them in sequence as I moved them around the background(Fig.6).

For the cut out background, I didn’t have enough room in my animation machine to make it in the same way I did the hand drawn, like a printer every frame. Instead, I made it in about 1-3 metre strips, then loaded it on to the rollers. Which was mighty fiddly with the delicate pieces, I’d recommend using some sort of transparency to back the cutout artwork if you’re loading it onto a roller. Then the process was more or less the same as with the hand drawn, but the separate pieces were made in batch, about 10-30 frames at a time, as opposed to frame by frame.

With all the techniques I used, one important part of how the film was made is that I only ever thought about 10-30 frames ahead. There was an overarching narrative of the shifting landscapes, going from countryside to city, that had been knocking around my head for a while, but the story in the film developed as I made it. This gave me the freedom to move about as I pleased, which also made it much harder to make mistakes as you can’t really go wrong when there’s no right way to go.

It also meant that I really had to rely on the music as I was going. Narrative shifts could hit with the changes in the music, the tone of the music decides where we’re going and it provided solid beats to sync actions up to. A combination of listening carefully and examining the waveform in DragonFrame as I went along. The whole film was essentially directed by the music.